A thick stack of black and white photographs flutters to the floor. A man stands over the jumbled pile and, looking past bent corners and nibbled edges, sees dozens of faces staring up at him. These faces are vaguely familiar—an old neighbor, a distant cousin, an aunt who used to spend summers with him. Some photos land face down and, from his height, the man can just make out the names and dates scribbled in purple ink across the backs.

He kneels down and, with the tips of his fingers, quickly rakes the photographs into a haphazard mound. He leans over it to inspect the faces more closely and immediately a voice begins whispering in his ear. Memories begin to flood the room. But these memories are not his own; they belong to the men and women in the photos. This voice anchors them to a story, breathes life into their stoic faces and makes their one-dimensional images come alive. But it also transfers the crushing weight of their memories onto this man’s shoulders.

In these memories lie the aching pain and unrelenting torment of deracination and exile. Although this suffering is not his own, he treats it as if it were an indelible part of his personal experience, silently assuming the burden of memory and selflessly disregarding its psychological toll.

Krikor Beledian: Agent of the Armenian Diaspora

This scene makes up the final pages of Krikor Beledian’s novel Seuils [Thresholds]. Published in Western Armenian in 1997 and translated into French by Sonia Bekmezian in 2011, Seuils is the first in a series of semi-autobiographical narratives exploring facets of the author’s childhood in Beirut and the first of his novels to be translated into any language. Beledian, born in 1945, is one of a handful of writers who currently publishes creative works in Western Armenian—the branch of the language once used by Armenians in the Ottoman Empire and now used, to varying degrees, by their descendants scattered throughout the Middle East, Europe, and the Americas.

In the early years of these diasporan communities, Western Armenian continued to serve as the language of literature and culture, but with each passing generation the number of people with the linguistic dexterity needed to write in the language has been dwindling. In 2010, UNESCO classified Western Armenian as “definitely endangered,” the second of five stages on the language extinction scale. A language reaches this stage when few children learn it as their first language. Beledian, however, writes as if blissfully unaware of this serious situation.

A prolific writer of poetry and prose since the 1970s, Krikor Beledian has become one of the few figures in contemporary Western Armenian literature—a scene that was once brimming with gifted writers who, like Beledian, took risks and experimented with the language, injecting it with new life after its near destruction. An academic as well as a novelist and poet, Beledian makes his home in France and teaches Armenian literature at the Institut national des langues et civilisations orientales (Inalco) in Paris. He has published novels, critical essays on Armenian literature, and collections of poetry, as well scholarly volumes on Armenian history and literature.

Beledian silently proclaims his exceptionality as a writer not only in the choice of Western Armenian as his sole language of artistic expression, but in the way he treats well-worn tropes in what he calls Armenian diaspora literature—writing by diasporan Armenians about diasporan Armenian experiences in languages other than Western Armenian. He squarely contrasts Armenian diaspora literature with Armenian diasporan literature—writing by diasporan Armenians about diasporan Armenian experiences in Western Armenian.

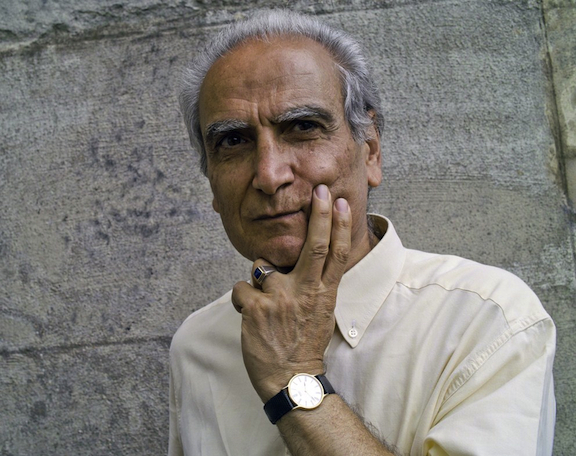

[Krikor Beledian. Image via the author.]

In Armenian diaspora literature, there is a tendency to dwell on the past and look to the villages and communities in the pre-1915 Ottoman Empire for direction on how present-day Armenian culture should look and feel. There is great concern for preserving this heritage to the detriment of valorizing Armenian experiences in the diaspora as they exist today. Beledian’s novels focus on giving diasporan experiences the consideration they deserve and asserting the vitality of modern diasporan Armenian identities. He does not allow his ancestors in the Ottoman Empire or the fledging Republic of Armenia in the Caucasus to prescribe how identity in the diaspora ought to be constructed. His novels encourage Armenians to see value in their own varied experiences, form their own understanding of Armenian identity, and not to look elsewhere for validation.

The literary influences on Beledian’s writing are emblematic of the melding of cultures inherent in the diasporan Armenian experiences whose authenticity he unwaveringly defends. In the words of literature scholar Talar Chahinian:

[Beledian’s] fiction demonstrates a style that is somewhere between the nouveau roman and the post-modern novel. His novels often shun punctuation rules, sequential plot lines, and reliable narrators. But though his novels’ forms are overwhelmingly inspired by French post-structuralist thought, their linguistic acrobatics and content are strikingly representative of the post-1915 Armenian diaspora, marked by a sense of chronological interruption and geographic dispersion.

Incorporating French influences into the core of his work is not an attempt to proclaim the superiority of European literature or to disparage the Armenian literary tradition; it is used to give a voice to diasporan experiences and allow them to speak through the structure of the novels.

Catastrophe in Translation

The structural skeletons of Beledian’s novels are filled out with inventive language that seek to revitalize Western Armenian as a literary language. When we read his work in translation—even in Bekmezian’s sublimely evocative translation—this attempt naturally goes unnoticed. Needless to say, a significant dimension is lost in translation when the original language is essentially its own character in the book.

The intrinsic challenges of translating Beledian’s work notwithstanding, Bekmezian’s French translation of Seuils does achieve one particularly critical goal: it acquaints a wider public with a literature intended to be read only by the Armenian community. Since Armenian is unique in that few beyond the community learn the language or achieve sufficient proficiency to penetrate its literature, reading Western Armenian literature in translation is like listening in on someone else’s therapy sessions. It reveals the collective joys, fears, preoccupations, and obsessions of an exiled people and delves deep into their psyches.

Nothing weighs more heavily on the Western Armenian psyche than what Beledian and a small group of other Western Armenian intellectuals call the Catastrophe of 1915—more commonly referred to as the Armenian genocide. Bekmezian’s translation shows us how such a shattering event is remembered and discussed within the community. Treated with subtlety and woven into the narrative like it is woven into the fabric of Armenian family histories, the Catastrophe in Seuils is not fleshed out in all of its grisly details as it would be if the book had been intended for an audience unfamiliar with the Armenian plight. It does not belabor the misery and adversity of the Armenians and has no designs on shocking readers into recognizing that it took place.

Beledian’s treatment of the Catastrophe is devoid of the sorts of underlying political motivations often seen in Armenian diaspora literature and in the public debate on Armenian genocide recognition. It looms, but it is never explained and does not need to be. For Armenians, it is shared history, common knowledge, a vivid part of their historical memory. Instead, Beledian considers the effect of the Catastrophe on the men and women who experienced it firsthand and on their children and grandchildren who have taken on that suffering as their own. How is this burden—disguised as family memories—passed along? Why do second and third generation diasporan Armenians still feel such an attachment to their pasts? Why do they still feel like an exiled people almost one hundred years and four generations after the Catastrophe?

Vicarious Suffering

In Seuils, Beledian probes these questions by exploring the stories and pictures of three women—his aunt Elmone, his grandmother Vergine, and his neighbor Antika—who were all driven out of their villages in southern and eastern Anatolia in 1915 and later settled in Lebanon. Their stories of pain and exile are told to an unnamed narrator by an omniscient voice that charges him with the responsibility of collecting, recording, and transmitting them.

The fragility of family history is a recurring theme in the novel. The narrator is empowered by the idea that, in an instant, he could burn the photographs and rip up the stories and nothing would remain of his family’s past. He is seduced by the power inherent in this role. The voice, however, implores him to keep the pictures and write down everything it tells him in order to keep the traces of the community alive. And he dutifully agrees.

But the narrator struggles with the fact that he has inherited this suffering. He rebels against what he perceives as a hindered sense of agency by filling in the gaps in his history with his own elaborate stories. In allowing the narrator to write original scenes in his family‘s past, Beledian comments on the malleability of history. He asks readers to question what they really know about their history and how they know it. History, he argues, is a constructed reality shaped by the people through whom it has been transmitted—people who pick and chose what should be remembered, what should be forgotten, and what should be embellished. Once a story reaches the present, its adulterated form may bear little resemblance to the lived experience.

This understanding of history feeds the narrator’s constructed relationships with the three women whose stories he has inherited. Not knowing any of them well, yet still feeling an obligation to record their experiences, the narrator invents a personal connection based on the pictures he holds in his hands and the painful stories whispered in his ear. Beledian uses the narrator to illustrate the illogicality of his bond: why does the narrator and, by extension, second and third generation diasporan Armenians with no direct connection to the Catastrophe, appropriate the suffering of their ancestors?

How can I talk about someone who I have not seen a single time? How can I penetrate her life and understand—beyond the legend, beyond the gossip—the thick, heavy existence of a human being whose scent I have not sniffed, whose hand has never brushed up against mine, who never pulled me into her lap, whose voice I have never heard and for whom I have absolutely no image in my mind.

These questions characterize the relationship between many diasporan Armenians today—living in places as diverse as New York, Paris, Beirut, Aleppo, Buenos Aires, London, Los Angeles—and their grandparents and great-grandparents. They are far removed from the trauma of the past, yet similar feelings of exile and alienation still persist.

Memory has taken hold of Armenians in the diaspora and affected how many understand themselves. Their past is a major source of strength and tends to solidify pride in their Armenian identities. But, as Beledian shows us, rooting identities in the past rather than in the present is problematic because there is only so much we can really know about our history. He illustrates this idea by emphasizing the narrator’s disorientation in the three women’s lives. The basic elements of their lives—composed of village songs he has never heard, dialects he has never spoken, places he has never seen, and a kind of pain he has never experienced—are foreign to him. Yet there is still a connection, still a bond that allows him to transcend all of these differences, however illogical it seems.

Breaking with the Past

Contrary to diasporan Armenians today who choose to remember their family’s past and make it a part of personal identities, those who survived the Catastrophe had no choice but to remember. They bore their pain not only psychologically, but physically. As much as diasporan Armenians feel the need to take on this suffering as their own, Beledian shows that there will always be limits to their understanding. Diasporan Armenians will never carry the traces of torment on their bodies and thus never truly understanding the extent of their pain:

How can you expect [the women] to return wearing shoes with their deformed toenails, their cracked heels, their wild feet that passed through and were burned by the sand, by the hills. You walk and walk, and it’s always the same sand, always the same caravan. There are no camels or bells, only and always this heat that burns your feet.

What diasporan Armenians feel is the suffering that took its first breath once those caravans reached their destination. It is not an inferior form; it is merely the second stage. Armenians born and raised in the diaspora will never truly be able to understand the first stage because the scope of the despair is too large to grasp. They will never know how it feels to be torn from the only life you have known and to be forced to rebuild it from nothing. They will never know the ache of hearing your children utter their first words in a language foreign to you or the unbearable longing for a place that no longer exists as you knew it.

The daily struggle to carry on faced by the first generation in exile was replaced by the second and third generations’ emotional, abstract struggle over identity and belonging. This is the second stage of suffering that diasporan Armenians experience. It is how they feel about what they have absorbed and imagined from the stories about the first stage. This second stage is merely a continuation, since it could not have come into being without the first. In other words, most diasporan Armenians would not be living in the diaspora if their ancestors had not survived the Catastrophe and endured the pain of exile. The suffering among diasporan Armenians is not simply composed of the assumed pain in the first stage. It is also composed of a lament for a life that could have been theirs.

Because of the Catastrophe, diasporan Armenians are permanently estranged from the linear history that their families had enjoyed in their ancestral villages for centuries. They will never know what their lives would have been like had that lineage continued uninterrupted. Unlike other children and grandchildren of immigrants, they cannot travel to see what life could have been like for them in their ancestral villages, because almost all traces of their ancestors have been erased in these places.

This abrupt change in direction and the shock of exile brought unexpected challenges within families: as Beledian illustrates, it led to an intensification of the divisions between Armenians who fled the Catastrophe and their children and grandchildren born in the diaspora. In Seuils, Beledian shows us how the new breed of Armenians born in exile were not necessarily valorized by the generation that fled. In the words of the narrator’s neighbor Antika:

Despite all of your efforts to convince these boys, they do not know the taste or the smell of Erzurum. It is not their air; it is not their water. Their flesh and bones are different.

It is true. Diasporan Armenians will never truly be part of that pre-1915 society that they exalt. It is not their experience, but by clinging to it and treating it as if it is, diasporan Armenians are attempting to take control over their past and create a history different from the one imposed on them. They are rejecting the idea of exile and attempting to blur differences between them and their ancestors. But, as Beledian clearly illustrates, the cultures of the diasporan Armenians and their ancestors are distinct.

It is precisely because these experiences are so different that the generation that was forced to flee wants to ensure that their stories are not forgotten, no matter the toll it may take on future generations:

She fixes her eyes on mine and waits silently for a moment. She then tries to find the lost thread, the word that has been lost since the old country. Did she reserve this role of custodian for me—the role of learning the legend by heart, of someone to pass on the same story and bring it to a close? Maybe she was convinced to pass on her memories because telling them allows her to survive? Otherwise, how can I grasp why she describes the most painful moments…without backing down and without any attempt to protect me from the violence of her life?

The feelings of estrangement and exile still alive in many second and third generation diasporan Armenian communities are linked directly to this idea because each generation is expected to bear the burden of the past. The baton cannot be dropped until it is passed onto the next generation, with all the painful memories and unbearable sorrow securely intact. This idea has been so ingrained and the responsibility has been couched in such grave terms that to drop the baton means breaking the chain that stretches all the way back to 1915.

Beyond Logic and Reason

In Seuils, Beledian asks Armenians—and now, thanks to the French translation, other readers who carry the pain of deracination—to consider the burden of the transmission of family history and the effects it can have on the extension of suffering.

He is not trying to convince readers to liberate themselves from their pasts or to abandon their family memories, but simply to be conscious of how memories have the power both to shape and paralyze.

***

Sorting through the pile of photographs, the narrator sees one of his Aunt Elmone and her granddaughter, Dzaghganoush. He is puzzled. He was sure that Dzaghganoush had been born in France and had never met her grandmother. He picks the photograph out of the pile and takes a closer look. A faint line shows that two photographs from two different decades have been superimposed. Grandmother and granddaughter had never been on the same continent, let alone in the same room, but here they stand side by side, spurning any sense of chronology or logic, to spend eternity together. By bearing the suffering of their grandparents and great-grandparents, diasporan Armenians are looking for this kind of closeness—a connection to their past to convey their respect for those who sacrificed so much for them.